Moisture wicking properties: how to lose them, how to boost them

Textile professionals are a lot like normal people. They can’t be compared. What makes one manufacturer extremely happy causes a bad day for the other. This certainly applies to moisture wicking. For some textile products, the feature is helpful, as it helps wearers stay dry and ventilated. But when you produce PVC coated fabrics, moisture wicking properties are the last thing you need. Now, how do you support the moisture wicking properties of textiles that need it? How do you reduce this effect in the ones that don’t? And what’s the role of auxiliaries in this story? We’ll tell you here.

How does moisture get wicked anyway?

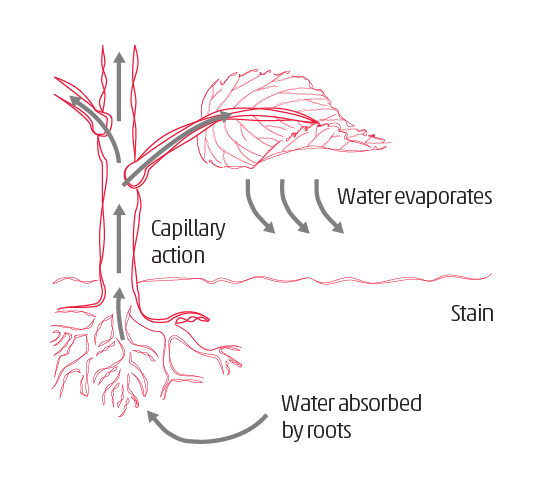

Moisture wicking runs on capillary action. This phenomenon transfers moisture through hydrophilic material, so that it can be pulled out or up. Trees are really good at it, as their roots use capillary action to soak up water from the ground (see the picture below). They aren’t connected to the electric grid, neither do they run on batteries; it’s a natural process. When you translate this to textiles, it’s the hydrophilic fibres that are responsible for the capillary action. They take up the moisture, adhere it through their fibres and transport it out, where it evaporates. This process is what we call moisture wicking. Textiles with moisture wicking properties are particularly suited for sportswear, as they pull the sweat away from the body to the open air. This cools down wearers and makes them feel more comfortable.

Moisture Wicking fibre: which fibre is best at moisture transport?

Not all fibre types have a natural talent for moisture wicking. By nature, polyester can only retain up to 0.4% of moisture. That means there’s barely any capillary action. Cotton can retain to 7%, which is already much more. This explains why polyester shirts can feel very uncomfortable in high temperatures. Shirts made from cellulosic fibres (cotton and especially linen) make the heat more bearable. However, this is only true for the first couple of hours. As cellulosic fibres also really like to hold on to water, meaning clothes will get wet and heavy after a certain amount of time (or when wearers work out). This is why not cellulosic fibres, but polyester fibres treated with a special finish are most suited for moisture wicking. Their inability to hold on to moisture combined with the added moisture wicking properties result in a fast transportation of sweat, leaving the wearer dry and comfortable.

Why is moisture wicking is not always a good thing?

This brings us to a very important part of this article: not all textiles should have moisture wicking properties. The feature comes in very handy when you are producing sportswear, camping tents or any other piece of textile. Those textiles need to transport a significant amount of moisture to keep the users dry, comfortable and ventilated. But when it comes to fabrics for continuous outdoor use, like PVC coated fabrics for truck tarpaulins and tensile structures, moisture wicking properties work counterproductive. As PVC coated fabrics tend to hold on to even the lowest amount of moisture, they start to absorb dirt and damp around the edges and seams or during use, when cuts and abrasion appear. Moisture isn’t able to transport out through the PVC coating. Resulting in mildew and weakening of the adhesion. This is why textile manufacturers are divided into two camps: they either need more moisture wicking properties or they need to get rid of it.

How to Create moisture wicking

You can add moisture wicking properties to your fabric in a natural and a technological way. Polyester becomes more breathable by weaving hydrophilic fibres into hydrophobic ones. This way the moisture is drawn to the hydrophilic fibres and transported out through capillary action. Another option is to change the structure of the polyester fibres during the extrusion process and turn them into more regularly structured, trilobal fibres. This is a great start, but often, fibres need a little more help in the form of chemical modification. In this case, you apply a hydrodynamic finishing agent to add moisture wicking properties to the fabric. This boosts the transportation of moisture and helps you meet your customer’s requirements (or better: desires).

What is an anti-wicking treatment?

Modifying your fabric with an anti-wicking treatment is a little more complex, mainly because you have to stop an entire process instead of boosting it. If you want to avoid moisture wicking, you probably produce textiles for outdoor use such as truck tarpaulins, tents and pool covers. This means that you need a strong and durable finish that can endure storm, rain and sunlight. Until recently, anti-wicking treatment was only able to slow down the capillary action by adding a finish to the outer layer. This was fine but not ideal. The good news is that our experts were able to develop a finish that completely stops the wicking process from the inside: a huge leap forward, if we may be so bold.

“TANA®COAT AWP barely degrades; it keeps its hydrolysis resistance for many years, even in very moist, cold or warm climates” – Peter van Brunschot, Business Development Manager Performance Coatings

When do you have to wick or not to wick?

Now that you know all about capillary action, moisture wicking properties and anti-wicking properties, it’s time to tell you a little more about our wicking and anti-wicking treatments. To boost moisture wicking properties, our experts created TANA®FINISH HPX: a hydrodynamic finishing agent for synthetic fibres. If you want to stop the wicking process, TANA®COAT AWP is your weapon of choice. “Not only is it the first no-wicking treatment for PVC coated fabrics for outdoor use”, explains Peter van Brunschot, Business Development Manager Performance Coatings, “it also barely degrades. It keeps its hydrolysis resistance for many years, even in very moist, cold or warm climates.”

Find out more

Clearly, there’s a lot that you can do to boost or avoid moisture wicking. But we can imagine you have questions regarding your own development process. If you want to find out more about our solutions to stimulate or stop moisture wicking, download the TANA®FINISH HPX or TANA®COAT AWP information brochures on the product websites.